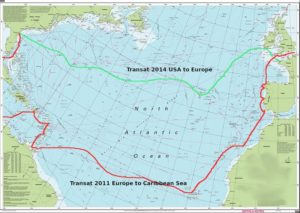

Transat West to East in 2014

(den här artikeln finns endast på engelska tyvärr.)

Preparation May 2014

In February I returned to my boat in Florida. The trimaran which I have, first floated in 1976 and was built to win the OSTAR race that year. It is a proven boat and able to make an ocean passage. I had found my way to Florida over a period of two years. First down from Sweden, via England, Spain and Portugal and over to the Eastern Caribbean, with a stopover on Grand Canaria, as well as a brief stop on one of the Cape Verde Islands. After the season in the Caribbean I went to South- and Central America for some time before making the passage up to the USA via Cuba and the Cayman Islands, arriving in April 2013. I left my 39-foot trimaran in Florida for almost one year because of sailing another boat across to Europe.

Jacksonville rainbow

Finally, after such a long time away, I was back on board my boat which always gives me a sense of relief. Now I could get to work preparing for my 9th passage across the Atlantic. The fact that the boat had been swinging on a mooring on St.Johns river for nigh on a year, meant a lot more work before any sailing at all could be done. The veritable oyster farm, growing on every available square inch of hull below the waterline, would give the boat the handling capabilities of an artificial reef, and that is unacceptable. In these situations my only option is to don a mask and snorkel and slowly chip away at the well secured and persistent sea-life with a scraper; my eyes straining to see anything at all in the murky river waters.

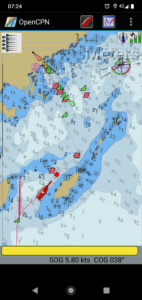

An assortment of other odd jobs required doing, as invariably is the case. I started to prepare the deck for a new coat of non-skid paint. I also checked all the electronics in the mast; the VHF areal and the tri-colour to be precise. I found, even though I’d left one of my good socks as a sun-shield threaded over the tri-colour-come-anchor light, that the heat of the Florida sun had loosened the cap of the polycarbonate glass tube. That was easily put right with super-glue and I felt confident of my repair. It also gave me a chance to inspect the tri-colour bulb, which before my East – West transat in 2012 I changed from an incandescent 25 Watt to an equivalent brightness 3.5 Watt LED. The bayonet sockets are not ideal to securely hold the heavier LED bulb and I have had failures there in the past.

I will not go into all the things which I did in the month before leaving, but the weather was looking better all the time and I could start to feel excited about the voyage ahead! Evenings I spent with fellow boating friends on the banks of the St.Johns, and frequently we spied Alligators in the waters close to shore. I also spotted one swimming across the anchorage and right under my boat, where I still had a lot more chipping off of barnacles and oysters to do before I could sail anywhere. I contemplated asking one of the Floridians to stand guard aboard with a some sort of firearm, I’m sure they know what the most suitable deterrent for Crocs is!

My main project had been to overhaul my auxiliary motor. It’s remarkable how many times a sailing vessel is stuck in harbour because of troubles with the engine, and I had had the same misfortune after the main baring on the drive-shaft had seized into a solid lump of corrosion, salt and old oil. Come mid-April the engine was finally ready to be started. After already having had to place 3 orders for spares, I really hoped not to have any more troubles and not to have to wait for yet another order of any more spares to arrive. I am happy to say that the starting was successful and the engine has run as well as anyone could wish for ever since then. Now I’d soon have no excuse to stay up that river in Florida any longer.

Sailing St.Johns

The crew arrived, and from then onwards for the next 4 months I would be living in the close quarters of a sailing boat with other people. We spent the last few days in quite a flurry of goodbye parties; for us and for other people also ready to leave for the passage to Europe. We hauled heavy bags of food from the shops and stowed everything safely. We made sailing trials and training on the river, as neither of my crew had any experience on yachts, least of all a multi-hull. The last items on the list of jobs were ticked off, and inevitably a few minor new points were added to it.

Eventually, on the 17th of May we sailed out of the river entrance on a good course ESE, at the fun bouncy, skipping pace of a multi-hull. Seasickness was not a problem, but little did I know then that we’d not get further than 200 miles from Jacksonville in the first 5 days.

The Voyage to the Azores. 26 days and 3600 miles.

Without the barnacles slowing us down, and the wind a good breeze from the North, we were making good distance East. My decision had been to position ourselves close to the same longitude as the Eastern Caribbean Islands and hence have a little more distance from, and hopefully to be in a better position to ride the low-pressure systems should they move off the North American continent over Bermuda. It was also the idea to avoid bad weather which frequently accompanies the gulf-stream in the form of thunderstorms and particularly choppy seas.

The wind only lasted for 24 hours before slowly dying away and we were left drifting North of the Bahamas, in beautiful sunshine and warm mid-Atlantic waters. Life on board was easy and comfortable for everybody. We all agreed that even though we weren’t actually going anywhere, being out there on the ocean and waiting for the wind was preferable to being anchored on the St.Johns River. It gave us all ample time to get used to the boat and establish our routines. That night was calm and without a moon and nothing disturbed the gay twinkling starry night sky.

Sailing East

The next day swimming was enjoyed by all, and the water could not have been more different from the murky waters of the river. I’m not sure what visibility there is out there because there’s no backdrop to measure against. All you’ll see is thousands of feet of salty Atlantic water, stretching away to deep blue depths below your boat. I found that I had missed large patches of shells and growth on the boat and spent some hours working to bring the former smoothness of the hull back to scratch. Within no time at all I saw several schools of different little fish, eagerly consuming all the little bits of edible sea-food raining down like snowflakes from the sharp edge of my scraper.

After 3 days of very little wind the trade-winds slowly filled in from the SE. With great excitement and joy we could begin laying the miles in our wake, put the fishing lines out and settle down for the long voyage ahead.

Saragasso Sea

The fishing is rarely good the first week at sea when on the route to Europe, not because there are no fish but because of the large quantities of Saragasso seaweed. You almost instantly after deploying the lure will hook the orange-brown weed and after that no fish will be fooled by your lure and strike. At one point the Saragasso was present is such quantity that the sea became like a soup, and slowed us down to a crawl.

The course we steered brought us along the East coast of Bermuda a few days later. When we finally came close to that Atlantic Island of Bermuda we saw the condos, cars and gleaming yachts. The question of weather or not it was worth stopping took little contemplation and we set another sail and bore off across the Atlantic, not looking back. The unanimous vote of all aboard. We sailed under seagulls and over schools of fish. We caught Tuna one by one for each day, filling the frying-pan with fresh fish time and time again. Dolphins raced ahead of us, only to surge back again, sweep past our boat and leap out of the waves, smiling in their eternally youthful and boundless joy.

One evening, about a week after we left Bermuda in our wake, I spotted – to the North of us – the great bulk of what I for a second thought could only be a whale, but I then realized that it was the silhouette of a yacht – capsized and floating high in the water. I hove to with the jib and we crept closer in order to see what was afoot, and if possible make sure of precisely what yacht it was before sunset brought the ocean into darkness. We drifted past very close, and took many photographs. We also hailed and shouted across the water, but it became apparent from the condition of the vessel that she had been adrift for a long time. However, I was amazed when I later found out precisely how long that trimaran had been drifting, and relieved to know that all of her crew had made it safely back to land.

The trimaran we found had capsized in a particularly violent squall off the coast of Bermuda in June 2010, and had now moved about 700 miles further East, but then, being stuck in the center of the North Atlantic high-pressure system, found herself drifting in the same area for years. And from all what I could tell she will probably be out there drifting for a long time yet. We sailed on and left **Region Aquitaine** alone under the darkening sunset sky.

Region Aquitaine

After three weeks at sea we had all settled down to the routines of keeping watch, cooking, sleeping and taking turns filling buckets with fresh, and now quite cold, seawater for daily showers on deck. The boat, without autopilot, required someone to be at the helm most of the time, but for about one third of the trip she self-steered under the balancing forces of her sails.

The Saragasso sea lay far behind us and now the fishing was good. Many days we did in fact not bother trawling a lure and instead made meals with rice, beans and lentils. Most of the canned food remained untouched, and I like to know that I have ready-to-eat food on board should the stove break halfway across the Atlantic. Being in a situation where you are forced to eat dried foods and potatoes uncooked is not much fun. I had experienced that during two weeks, while on passage in the South Atlantic some years prior.

Mar Lena

One early morning we spot a light ahead of us which could only be the masthead lantern of another sailing boat. Then, as the sun burst out from behind the clouds on the horizon, we could make out the pure white of sail canvas and soon thereafter the hull of a yacht some miles ahead of us. We had breakfast and coffee, all the while getting closer to that other lone vessel on the open ocean. Soon we were talking on the radio and taking pictures of each other, both rolling along under full sail. I found out that we planned landfall on the same island in the Azores and we decided to meet up for a beer and to exchange the pictures we took. We arrived 4 days later, us only 10 hours ahead of them.

Three Isles of the Azores.

An island, the first sight of land, peaks out of the sea in the East, and rises higher after the morning sun as we approach. Clouds are arranged in the sky, wispy, windswept in the high altitudes and amazingly clear against the dawn sky. The breeze over the spinnaker and the sound of the gentle rush of water along the hulls is savoured by us all, because soon it is known that the perpetual motion of the last few weeks will have to come to an end.

Land Ahoy

The island is one of many in the Azores, Isla das Flores is the name she has been given, and very suitably we are soon to find out; it meaning Flower. It is delightful to see and sense land ahead after weeks of ocean, but a quiet whisper at the back of your mind stirs up feelings of sadness too; that all is over, you are back to what is. How is all the unchanging solidity of land possible? Where do I fit in, how do I join again, how can I leave this world of my own?

Cliffs fall steeply down into the sea along much of the coastline, and many a mountain stream can be seen as a waterfall onto the sea creating a light mist and sparkling light. Flores is only a small island and 4000 people have their homes on the green lands of her interior, amongst trees and hills, along the winding roads.

The only practical place to safely stop with a yacht is Puerto das Lejes in the South. One must anchor in deep water, but will be protected from anything other than a Southeaster. Since 2012 there is an inner yacht and fishing harbour which for boats of limited length and beam will be safe mooring in all conditions. From the harbour one can see the whole bay, most of it lined by cliffs. The town, starting at the great harbour breakwater, struggles up one side of the mountain and disappears over a crest.

Flores Anchorage

Soon after anchoring we have the dinghy out and ready to go! We all pile in and begin the paddle to land, the last tiny little bit of voyage of the Atlantic Ocean. Climbing from the dinghy and up the ladder of the harbour quay land definitely feels solid and formidable. The cliffs around showing off that land definitely can reach higher than any wave of the sea. We stop a while at the top of the quay and look back at our little yacht sitting so calmly upon the surface of the harbour water. Looking at that view really felt like a great moment and the magnitude of what we had achieved could really begin to sink in. Below our feet some large fish flick their tails and swim in lazy circles under the harbour waters, little crabs sidle along cracks in the quayside. We smile at each other and then turn our back on the sea and face the town, the lush green trees and plants and the volcanic mountain behind; to begin our walk up the hill, on rather unsteady sailors legs.

The houses, walls and roads are very neat and well kept, the flowers are everywhere one could wish, bright in colour and looking beautiful. There’s everything in Lajes, from supermarkets to a library and internet-cafe, restaurants, convenience stores, banks and pubs – only the lastnamed number more than two.

Mostly everything is imported to the island by a supply ship docking once every two weeks in the harbour. However bread is baked on the island; the large, round, brown bread is nice for days after purchase and great for an onward passage! Fish is also plentiful whenever one of the colourful fishing boats arrives back from sea. Many of the homesteads have a chicken pen, maybe a goat in the yard or a field of lush green potato plants. Cows wonder in the highlands, a heard of sheep can bee seen as a white speckle the against the green grass of a hillside.

As a visitor one feels that something, still in the past, exists there on Flores. It is not only the way of life, but also the relaxed socialising, the clothes and, as I noticed, the local FM radio station; they all contribute to the strong sense of history and permanence

Fish Delivery

Walking up the steep hills and over the brow of a hill, and then to follow the road down the other side to one of the large volcanic lakes is a breathtaking walk. Especially after living at sea level for weeks. I was lucky enough to have a lorry stop beside me and the driver invite me on board. Driving up the next hill at walking speed, in low gear, we would reach the top of the island, or so I until we reached the crest and my gaze fell on the land and mountains beyond.

The island is quite high, and pushes into the cloud, often views will be shrouded in rolling, damp mist. The land up high reminded me of the moors in the Southwest of England, Dartmoor maybe. Scrubs and steely gorse bush grow dotted around the weathered, grass-tuft mountainsides, occasional gray shapes of rock and boulders act as landmarks.

Flores Waterfall

The driver of the lorry is a man in his late 30’s. The truck-bed is full of gravel being brought up for a new road which is supposed to lead to a viewpoint for tourists. Once we reach the construction area I find there to already be an adequate road there. I ask him then; “Why are you building a road, what is it for?”, but realise that actually the only answer is that there is no other work for this lorry driver. It seems that many people are government employed on the island. This keeps the island looking very neat and tidy, without a doubt, and the people seem mostly very content in their way of life.

From conversation I had with people I learned, other than the significance of cattle ownership, that actually there are not enough women on the island. I guess that the girls of Flores move away more easily than the men… to continue education or work in mainland Portugal. I suggested to the guys that they go to Brazil and bring back some women from there, they speak Portuguese, and without a doubt would be a great addition to the island!

Back at the anchorage that evening we are all awed by the beautiful place we have just seen. We listen to the surge of the sea breaking along the rocks at the base of nearby cliffs, the stars are bright in the sky. All along the bay seabirds start up a racket of bizarre calls bursting from nesting places high up on the cliff face. Like crazed children their voices carry in the night air. I say crazed, or demented, because the sounds they make are very odd, but they make us laugh; what on earth are they sounding so funny for! How does a sound like that mean anything?

Finding crew.

The majority of all the yachts which have just made the passage from the Caribbean or North America will stop in the Azores to resupply, explore the islands and wait for a good weather window to make onward passages to various destinations in Europe. Many of the people who have come across the Atlantic as crew will perhaps be out of time and have to fly out. Others will want to change to yachts heading to other destinations, so you will always find skippers looking for crew, and sometimes crew looking for yachts. Several hundred yachts make the passage each year in spring and early summer, and during the season all the harbour pubs in the Azores are bustling with sailors.

Horta Docks

I myself found myself short-handed because one of my crew had to return home to work. Hence I had to find somebody new to again make three of us on board and then sail the boat to Ireland.

The main cruising destination is Horta on the Island of Faial, and I though that that would be the logical place to look for any willing hands. We made the 120 miles from Flores to there overnight, with perfect wind, and the next morning anchored in Horta. Close by and visible behind the harbour is the Caldera del Diablo which is a crater formed by a powerful volcanic eruption in the early 1900-hundreds. Across the sea, about 10 miles distant is one of Europe’s highest mountains; Pico. Pico, that sits there far out in the Atlantic, reaching thousands of feet above the sea, with a perfect volcanic crater summit. The mountain is often sheathed in a white, flowing cap of cloud which is then blown off in streaks by the trade-wind. It all serves to make a fantastic backdrop to the harbour.

Pico

Horta is actually one of the top three busiest hubs of passagemaking yachts in the world and quite a spectacle to behold. Boats are coming and going all the time and sounding their fog-horns in salute, flags fly from a hundred masts, colorful drawings made by sailors, commemorating their boat and crew, fill the walls, walkways and quaysides of the harbour. People are lifting sails on and off their boats, carrying cooking-gas bottles away to be filled. You will see sailors climbing masts to make checks and repairs and everywhere there are groups of people sitting around laughing and watching the goings-on. In the evening people wander from party to party and boat to boat to bub and taking their time savouring feelings of a happy return to land, and the excitment of soon setting sail again and heading out on the next passage. Everywhere can be heard talk of the weather, how good the fishing was, and stories of the adventures people have had.

Unfortunately for us we had no luck in finding anybody who could make the trip to Irland, although we had some promising leads. After three nights in Horta we decided to sail to Iliah Sao Jorge, about 25 miles away, to try our luck there, and to get away from the hustle and bustle of Horta again.

As it turned out we would find our crew there in Sao Jorge in the tiny port of Velas. Furthermore, two nights later, as luck would have it, the winds turned in our favour and we departed for Ireland.

Azores to Ireland. 1400 miles and 13 days.

The seas around the Azores have many ocean currents that are home to great quantities of fish, and also make up migratory routes for whale and dolphin which frequently can be seen in great numbers. We had dolphin species such as the common dolphin and bottle nosed dolphin all around the boat on several occasions. A day out from the Azores two fin-whales passed very close by to look at us, breaching to take breath and exhausting great mist-like plumes of water, only to return shortly thereafter and swim close under our bows. They came back several times and repeated the maneuver before heading off South with great lazy strokes of their tail-fins.

The seas around the Azores have many ocean currents that are home to great quantities of fish, and also make up migratory routes for whale and dolphin which frequently can be seen in great numbers. We had dolphin species such as the common dolphin and bottle nosed dolphin all around the boat on several occasions. A day out from the Azores two fin-whales passed very close by to look at us, breaching to take breath and exhausting great mist-like plumes of water, only to return shortly thereafter and swim close under our bows. They came back several times and repeated the maneuver before heading off South with great lazy strokes of their tail-fins.

We were making good distance North and the route decided upon would ensure we kept far out to the West, far from mainland Europe. Also, more importantly, it would keep us out the Bay of Biscay should an Atlantic low-pressure come over us and force us to turn East.

As it turned out we were caught in just such a storm 5 days before reaching Ireland and I was happy to have all that sea-room, and could sail along with the strong winds and large Atlantic waves without the worry of land ahead of us. It calmed down sufficiently, after 2 whole days of quite severe weather, for us to turn back onto a course for Ireland and the Fastnet lighthouse.

During the storm I we had constant rain, and in the cabin you could hear the wind whistling loudly in the mast. Breaking waves hit the back of the boat, the spray flying up high in the air, and anything not properly secured in the boat crashed to the floor and broke. That is why glass can be hazardous on board a boat at sea, especially if the crew is barefoot and it is night time and dark.

The waves made it very difficult to keep the boat pointing exactly down-wind, and because of that we were running the risk of accidentally turning side-on to the waves. If that happened, and a breaking were to hit at the wrong moment, it could damage the boat. Furthermore the wind-chill factor, together with flying spray and rain quickly made anybody outside very cold and tired and it became apparent that we had to do something about the situation.

I carry two very long ropes with miniature parachutes sown onto them at 4 foot intervals, it is what’s known as a drogue system, and once deployed behind the boat we found it to work exceptionally well. I had one of the ropes on each side of the cockpit of the boat, and by feeding them out slowly I could reduce our speed and thus give us much better control over the boat. Like a volume-control I could adjust how fast we were sailing. Before the drogue was deployed we were going at 8 or 9 knots, even though there were no sails set at all. After I deployed the drogue we were making a much more comfortable 3 to 4 knots, and that made all the difference in the world to my peace of mind and our safety.

We arrived to Schull in Ireland, on the remnants of the low-pressure, the sun was shining again and we were finally able to dry everything, mattresses, jackets and sleeping-bags were spread out on deck, the drogue was strung like bunting, crisscrossing between the mast stays and creating quite a spectacle to the Irish folk watching us. Of course, a Guiness and a warm pub was now on everybody’s mind.

Starburst cloud